August 1999

(To request a bound copy of this report, click here.

To see a complete list of Milbank reports, click here.

When ordering, be sure to specify which report you want,

your name, mailing address, and phone number.)

Foreword

This report describes a program in the schools of Lincoln County, Oregon, to reduce the incidence and consequences of violence among young people. The program in Lincoln County implements the Resolving Conflict Creatively Program (RCCP), an initiative of Educators for Social Responsibility (ESR). RCCP is now used in 350 schools that serve 150,000 young people in nine states.

Children who participate in RCCP increase their ability to manage emotions and resolve conflict. Research suggests that the program has had a significant positive impact on the development of children who received regular instruction (an average of 25 lessons) in the RCCP curriculum. These children saw their world in a less hostile way and were more likely to choose nonviolent ways to resolve conflict. The program was equally effective for boys and girls and for low- and high-risk children. Preliminary evidence suggests that children who received substantial instruction in the RCCP curriculum performed significantly better on academic achievement tests and were reported by their teachers as less aggressive than all other children. The most positive change occurred in children who received regular instruction over two years.

If it is sustained, RCCP could contribute to reducing violence and hence to improved public health in particular communities. However, the educators who are implementing RCCP are only beginning to collaborate with their colleagues in health, social service, and criminal justice agencies to reinforce what young people learn in the program.

This report describes the history of RCCP in Lincoln County and summarizes evidence that children and teachers believe that the program is successful. But the report also makes plain that practical methodologies have not yet been developed to assist other county and state agencies to build on childrenís experience in RCCP.

We invited Jean Cowan, a Lincoln County Commissioner, to review a draft of the report and to help us understand the potential for RCCP to help reduce violence. The three county commissioners support programs like RCCP, she said. However, it will be ìimportant to integrate RCCP with other activities in the communityî more effectively than is done at present.

Cowan also cautioned her colleagues in government as well as taxpayers not to expect immediate results from RCCP. Young people ìcanít use immediately everything we give them.î It will take time for them to ìinternalize the skills they acquireî in the program, she said. Moreover, her colleagues among elected officials and leaders of RCCP should acknowledge that ìitís a hard concept for the taxpayer to have to look at what weíre building and growingî as well as the ìoutcomes we need tomorrow.î

This report is the result of collaboration between the Milbank Memorial Fund and the RCCP National Center of ESR. The Fund is an endowed national foundation, established in 1905, that works with decision makers in the public and private sectors to carry out nonpartisan analysis, study, research, and communication on significant issues in health policy. The RCCP National Center, operating under the auspices of ESR, helps young people develop through education convictions and skills that help to create a world that is safer and more just.

The Fund and RCCP began to collaborate at the suggestion of Mark Rosenberg, director of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). RCCP staff joined officials of several states, the CDC, and the American Medical Association to explore the implications for policy of Daniel Golemanís 1995 book Emotional Intelligence in a meeting convened by the Fund. As a result of that meeting, Peggy Rosenzweig, a member of the Wisconsin Senate, invited staff of RCCP and the Fund to join her and colleagues from government and the private sector to assess interventions against violence among young people in Milwaukee.

We subsequently convened leaders from several RCCP sites with mayors, a juvenile court judge, legislators, and public health officials to discuss the lessons of the program for policymakers. Participants in that meeting suggested that stories be written describing RCCP in different communities. RCCP leaders from Lincoln County and Pam Curtis of the Oregon governorís staff volunteered to assist a journalist to write the first description.

The Fund engaged Burness Communications to conduct interviews in Lincoln County and Salem, the state capital, and to write the report. Teri Larson conducted the interviews and drafted the report, in collaboration with Andy Burness. Ellen Anderson of the Lincoln County School District arranged Larsonís interviews in the county; Pam Curtis made arrangements in Salem. Persons interviewed, participants in the meeting that led to writing this report, and the reviewers of the manuscript are listed in the Acknowledgments.

Daniel M. Fox

President, Milbank Memorial FundLinda Lantieri

Founding Director, Resolving Conflict

Creatively Program National Center of

Educators for Social Responsibility

Acknowledgments

The following persons participated in meetings to plan this report and/or reviewed it in draft. They are listed in the positions they held at the time of their participation.

J. Lawrence Aber, Director, National Center for Children in Poverty, School of Public Health, Columbia University; Ellen Anderson, Project Coordinator, Lincoln County Primary Prevention Project (Lincoln County RCCP), Newport, Ore.; Cassandra Bond, Executive Assistant to the Director, Resolving Conflict Creatively Program (RCCP) National Center of ESR, New York; Jean Cowan, Lincoln County Commissioner, Newport, Ore.; Pam Curtis, Policy Analyst, Office of the Governor of Oregon; Larry Dieringer, Executive Director, ESR; Cathy Dunham, Program Director, Robert Wood Johnson Community Health Leadership Program; Sherrie Gammage, Co-Site Coordinator, RCCP, New Orleans, La.; Ernestine Gray, Judge, Orleans Parish Juvenile Court, New Orleans, La.; Larrie Hall, Principal, Roosevelt Middle School, Oceanside, Calif.; Carolyn Hart, Discipline Liaison, Instructional Services Center, Atlanta Public Schools; David C. Hollister, Mayor, Lansing, Mich.; Michael Kerosky, Supervisor, Student Assistance Program, Anchorage School District, Anchorage, Alaska; Linda Lantieri, Founding Director, RCCP National Center of ESR, New York; Lloyd F. Novick, Commissioner of Health, Onondaga County Health Department, Syracuse, N.Y.; Tom Roderick, Executive Director, Metropolitan Area New York Chapter, ESR, New York; Peggy A. Rosenzweig, Member, Joint Finance Committee, Wisconsin Senate; Jinnie Spiegler, Associate Director, RCCP National Center of ESR, New York; Arlen Tieken, Director of Education, Lincoln County School District, Newport, Ore.; Joan Wagnon, Mayor, Topeka, Kans.; Carol Wilson, Director, Principalís Center for the Garden State, Princeton, N.J.

The following persons were interviewed during the research undertaken for the preparation of this report; they are listed in the positions they held at the time of their interviews. Ellen Anderson, Pam Curtis, and Linda Lantieri arranged and coordinated many of the interviews in addition to being interviewed themselves.

Micki Bedlington, Teacher, Yaquina View Elementary School; Ken Breeding, RCCP Coordinator, Vista, Calif., and Consultant, ESR; L. Craig Campbell, Senior Vice President & Corporate Counsel, The Victory Group, Inc.; Debby Clark, Teacher, Sam Case Elementary School; Dennis Dotson, Lieutenant and Station Commander, Oregon State Police; Jay Fineman, Chairperson, Lincoln County School Board; Mark Gibson, Policy Advisor, Healthcare, Human Services, and Labor, Office of the Governor of Oregon; Dee Haddon, parent, Mary Harrison School; Jane Harrison, Senior Program Associate, RCCP National Center of ESR; Haiou He, Senior Research Analyst, Oregon Department of Human Resources; Doug Hunt, former Chairperson, Lincoln County School Board; Kathy Kollasch, Principal, Oceanlake Elementary School; Roy Kruger, Senior Associate, Assessment and Evaluation, Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory; Theodore Kulongoski, Justice, Oregon Supreme Court; Skip Liebertz, Superintendent, Corvallis County School District; Sue McVeigh, Teacher, Mary Harrison School; Greg Peden, Director, Criminal Justice Services Division, Oregon Department of State Police; Therese Price, parent, Arcadia Elementary School; Mary Riley, Community Grants Specialist, Town of Manchester, Connecticut; Jeanne St. John, Principal, Mary Harrison School; Arlen Tieken, Retired, formerly Director of Education, Lincoln County School District; Beverlee Venell, Director, Criminal Justice Services Division, Oregon Department of State Police; Grace Wiesner, Teacher, Waldport Elementary School; Tom Zandoli, Principal, Yaquina View Elementary School; and students of the Lincoln County School District.

Introduction

Newspapers and magazines, radio talk shows, and television news programs are proclaiming an ìepidemicî of violence in our schools. The stories they report often dwell on the horrific details of recent shootings in public schools. The reports typically profile young lives cut short by their classmatesí violent acts and recount heroic tales of witnesses who tackled the gunmen and saved lives. In every story, the question is asked, ìCould these unnecessary deaths have been prevented?î

This is not one of those stories.

Instead, it is the story of a rural Oregon communityís efforts to promote peace and teach its young people alternatives to violence through the Resolving Conflict Creatively Program (RCCP)––a nationally recognized, comprehensive school-based program in social and emotional learning that focuses on conflict resolution and intergroup relations. This story recounts how the residents of Lincoln County determined that RCCP is the right program for its young people. It also reveals how the county took advantage of a state commitment to juvenile violence prevention and, unlike any other community in the country that has introduced RCCP, secured state funds to implement the program over a four-year period. It is also the story of how well RCCP––a program that began in the large, racially diverse, urban New York City Public School System––is working in Lincoln County, Oregon, which is a comparatively small, largely white, rural community.

The Lincoln County School District did not undergo random acts of violence that left survivors wondering, ìWhy did this happen?î Rather, local residents were initially motivated to adopt preventive action by disturbing trends, such as the high number of juvenile arrests, school dropout and absentee rates, and levels of alcohol and illicit drug use and abuse among teens, which indicated that Lincoln Countyís youth could benefit from a school-based program designed to prevent violence and promote peaceful communities of learning.

In fact, national statistics demonstrate that school-aged students nationwide may benefit from such a program. In May 1998, a school violence fact sheet produced by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stated: ìLess than one percent of all homicides among school-aged children occur in or around school . . . yet recent violent events indicate we need to redouble our efforts to prevent violence in schools at the same time we address violence in the larger community.î Further, a survey conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics in the 1996-97 school year uncovered the following facts:

- Fifty-seven percent of public school principals reported that one or more incidents of crime and/or violence serious enough to report to the police had occurred in their school.

- Ten percent of all public schools experienced one or more serious violent crimes (defined as murder, rape, suicide, physical attack with a weapon, or robbery) that were reported to the police.

- Physical attacks or fights without a weapon led the list of reported crimes in public schools; about 190,000 such incidents were reported.

- Twenty percent of public schools reported six or more incidents of crime; 37 percent reported five or fewer incidents.

The Clinton Administration heralded the results of the National Center study by stating that school crime is down overall. It focused on the fact that 90 percent of public schools reported no serious violent crimes, such as robbery or weapons attacks. Unfortunately, this statistic ignores the fact that 10 percent, or almost 9,000 schools, do experience such incidents, and only 47 percent of schools experience no incidents of any type of crime. In addition, these statistics mask the fact that juvenile homicide still remains twice as common today as it was in the mid-1980s.

It is necessary to point out that Lincoln County, while deeply affected, was not motivated to action by the May 1998 student shooting incident at Thurston High School in Springfield, Oregon, which is about a two-hour drive from the county. That incident, which captured national headlines, occurred only very recently, whereas Lincoln County has been working actively on this issue since 1994. It is not the purpose of this report to hold up Lincoln County as a model of behavior that is superior to Springfield's example. Community leaders in Lincoln County are quick to point out that the incident at Thurston High School, and the outbursts at several other high schools around the country in the past year, could happen anywhere at any time––perhaps even despite preventive efforts. Shootings at schools are still rare occurrences that are perpetrated by young people who likely need even more support than can be provided by courses in conflict resolution skills. The point of a prevention program, like RCCP, is to teach all children how to manage emotions and resolve conflict constructively, rather than destructively, and to create a climate for nonviolence to flourish.

The Resolving Conflict Creatively Program is one of the nationís largest and longest-running, research-based school programs for resolving conflicts and fostering positive intergroup relations. Its goal is to promote caring, cooperative learning environments by reaching young people through the adults who relate to them on a daily basis in school, at home, and in their communities. In its comprehensive approach, RCCP moves beyond implementing an isolated educational innovation and focuses instead on changing the entire culture, both within schools and on the outside, as it seeks to engage the broader community in creating a safe haven for children.

RCCP promotes a new vision of education––one that recognizes that the ability to manage emotions, resolve conflict, and interrupt bias are fundamental skills that must be taught. According to Linda Lantieri, director of the RCCP National Center, ìWe can shift around young peopleís images of a hero and help them realize that the ëRambosí of this world, far from being heroic, are pathetic because they can think of only one solution to the problem. We can help young people realize that the highest form of heroism is the passionate search for nonviolent solutions to complex problems. Young people can learn to deal with their anger differently.î

RCCP currently serves 5,000 teachers and 150,000 young people in 350 schools nationwide, including the New York City Public Schools and 12 other diverse school systems in various stages of implementation: the Anchorage School District in Alaska; the Roosevelt School District in Phoenix, Arizona; the Vista Unified School District and the Modesto City Schools in California; the Atlanta Public Schools in Georgia; the New Orleans Public Schools in Louisiana; the Boston Public Schools in Massachusetts; the West Orange, South Orange––Maplewood, and Newark School Districts in New Jersey; the Lawrence Public Schools in New York; and the Lincoln County School District in Oregon.

RCCP began in 1985 when Community School District 15 in Brooklyn, New York, decided that it needed a ìpeace educationî program. The school district turned to two people for help in creating such a program. One was Tom Roderick, executive director of the New York chapter of Educators for Social Responsibility (ESR). ESR is a national organization whose mission is to help young people develop the convictions and skills needed to shape a safe, sustainable, and just world. Another was Linda Lantieri, then a curriculum specialist for New York Cityís Board of Education. The result of their collaboration was a pilot program, called the Model Peace Education Program, which was introduced successfully into three schools in Community School District 15.

The popularity of the pilot project led to an expanded program, first in District 15 and eventually in other school districts in New York City. The expansion of the program––which came to be called Resolving Conflict Creatively––was fueled by several factors: One was the commitment of the New York City Board of Education, which, once the pilot program was in place, immediately requested that it be extended to other districts. Another was an independent evaluation of the District 15 program, which found that student behavior was indeed changing as a result of exposure to RCCP lessons. A third factor was a nationwide surge in violence among young people. After several highly publicized juvenile homicides in New York, violence prevention became a high-priority political issue, and RCCP quickly became an item on the budget of the New York City Board of Education, where it remains to this day.

Once established successfully in New York City, it was only a matter of time before other school districts showed an interest in the program. The Anchorage School District in Alaska became the first district outside New York to express an interest in bringing RCCP to its schools. In 1993, under the auspices of Educators for Social Responsibility and with Lantieri as its director, the RCCP National Center opened its doors in New York City. The organization soon became a leader in advocating for social and emotional learning as an educational ìbasic.î

The RCCP Model

RCCP has evolved over the past decade from a small pilot program to a national model that can be replicated in any community. RCCP uses a broadly conceived strategy to create schools that are peaceable and effective communities of learning. It is characterized by deep, committed involvement over a period of time. The RCCP model includes the following components:

In RCCPís long-term vision, children enter kindergarten and immediately begin learning that differences are valued, feelings are accepted, and nonviolent approaches to conflict are the norm. When they enter middle and high school, these young people are role models for others in the community. By the time they become adults, they are ready to face the challenges that await them in the 21st century. They are prepared to succeed in multicultural workplaces. They are skilled in leadership that is rooted in social responsibility. They know how to listen, how to communicate, and how to resolve conflict in an atmosphere of caring and respect.

- Professional development courses introduce educators to the concepts of RCCP and provide training in the necessary skills; a staff developer follows up with several classroom visits to each teacher.

- Regular classroom instruction based on K-12 curricula teaches young people critical skills and concepts in social and emotional learning.

- Administrator training introduces strategies to help administrators use effective, democratic approaches to conflict and diversity issues and to support the implementation of RCCP.

- Support-staff training (for secretaries, bus drivers, lunch aides, etc.) helps these important members of the school community resolve conflicts with young people and colleagues.

- Parent training introduces fundamental concepts, skills, and strategies that parents and caregivers can use to create peaceable homes and reinforce what their children are learning in school.

- Peer mediation trains 20 to 30 students per school as mediators, who then help their peers to resolve student conflicts that arise.

- The development of trainers equips local leaders to implement and deliver each component of the program through a four-year mentoring process with the RCCP National Center.

Does RCCP Work?

In 1998, RCCP was the only school-based program highlighted at the White House Conference on School Safety, which was attended by President Clinton, Vice President Gore, and more than 200 educators, law enforcement personnel, counselors, and parents. In addition, RCCP and three other programs were chosen from a field of 250 violence prevention programs to be featured in a 1995 General Accounting Office publication titled School Safety: Promising Initiatives for Addressing School Violence.

The New York City RCCP currently is completing the most comprehensive evaluation conducted on RCCP to date. The evaluation, which is sponsored by the CDC and several private foundations, has three components: a short-term longitudinal study of the impact of RCCP on 9,000 children in 15 elementary schools during the 1994-95 and 1995-96 school years; in-depth interviews with teachers at a subset of participating schools; and a new management information system to track the implementation of the program.

J. Lawrence Aber, director of the National Center for Children in Poverty, is serving as principal investigator on the child impact study, for which researchers created age-appropriate surveys that were administered to children in their classrooms. These surveys were designed to measure problem-solving skills, aggressive fantasies, and hostile biases. Previous research has shown that childrenís scores on these measures are correlated with their actual behavior. The findings to date, based on year-one data, are that RCCP has a significant and positive impact on preventing violence in children who received a substantial amount of instruction in RCCP concepts from their teachers (on average, 25 lessons) during the school year. These findings indicate the potential of RCCP for successfully intervening in, and redirecting, childrenís developmental pathways that are known to result in later aggression and violence.

The preliminary findings of the CDC study echo the observations of previous RCCP evaluations. For example, an independent evaluation of RCCP in Atlanta, conducted by Metis Associates and released in 1997, found that RCCP has had a positive impact on program participants. According to project evaluator Stan Schneider, ìThe changes in measures we observed throughout the year of the evaluation were greater than one would expect in such a short time.î Specific findings included:

Another Metis evaluation, conducted in the New York City schools and released in 1990, found that 87 percent of teachers believed RCCP was having a positive impact on their students. The teachers reported fewer fights, less verbal abuse, increased self-esteem, more caring behavior, and more acceptance of differences by their students.

- Sixty-four percent of teachers reported less physical violence in the classroom.

- Seventy-five percent of teachers reported an increase in student cooperation.

- Ninety-two percent of students felt better about themselves.

- More than 90 percent of parents reported an increase in their own communication and problem-solving skills.

- The suspension rate at the middle school that was implementing RCCP decreased significantly compared with the increasing rate among middle schools that were not implementing RCCP.

- The dropout rate at the high school that was implementing RCCP decreased significantly compared with the increasing rate among nonparticipating high schools.

Welcome to Lincoln County, Oregon

Lincoln County, which occupies a thin strip of land along the rural Oregon coast, is prime whale-watching territory. Within the county are six distinct communities: the largest are Lincoln City and the county seat of Newport, and the smallest is a tiny inland hamlet called Eddyville.

The county is home to 42,200 residents from all socioeconomic backgrounds, and the population is largely white and composed of a disproportionate number of low-wage, working-class families who rely on tourism, forest products, and a declining fishing industry for employment. In 1996, the median family income was $7,500 less than the stateís median and $10,300 less than the national median.

Lincoln County currently is in its third year of a four-year plan to integrate RCCP into the countyís schools. There are 18 schools in the county––eight elementary schools, four middle schools, four high schools, one K-8 school, and one K-12 school. Total enrollment in these schools averages approximately 7,000 students each year. Currently, more than 45 percent of the countyís children qualify for free or reduced lunch.

Although violent juvenile crime is relatively rare in this poor, rural county, other types of destructive behavior among young people have increased during the last decade. Local police are being called more often to school campuses to address disruptive incidents among students. Higher numbers of young people are being arrested for property theft, vandalism, and consumption of alcohol and illicit drugs. Teachers are experiencing more serious discipline problems in their classrooms, and the county regularly records some of the highest school dropout and absentee rates in the state. In 1994, these trends prompted Lincoln County residents to take a long, hard look at their children and, although they didnít realize it at the time, to take the first step toward bringing RCCP to their schools.

The First Step toward Adopting RCCP

It was concern for the well-being of students, teachers, and the community at large that prompted then-Superintendent of Schools Skip Liebertz to convene the Commission on Student Violence and Discipline in May 1994. ìIt wasnít one serious, violent incident that prompted the formation of the Commission,î said Liebertz. ìIt was many little instances of rough behavior and low-level delinquency that seemed to be eating away at the edges of respect for teachers and school staff, respect for school and personal property. It was the type of stuff that we didnít want to escalate any further, so we pulled together a group of community representatives to assess the problem and determine how to correct it.î

Gordon MacPherson, a former state senator, Lincoln County resident, and parent, headed the commission. Its appointed members represented a broad spectrum of the community, and many were also parents; among them were a school bus driver, a state police lieutenant, the editor of the local newspaper, a juvenile court counselor, a school sports coach, a school principal, and a teacher. The group was charged with reviewing existing student discipline policies, determining the extent of discipline problems in the schools, and recommending ways to deal more effectively with the identified problems.

The commission held 12 meetings, during which it heard testimony from school administrators, teachers, other staff, and various community representatives. In addition, the commission held four public hearings in different communities to give parents, students, and other citizens the opportunity to participate. Subcommittees also visited other schools around the state and reviewed the codes of student conduct used by county schools.

In its final report, dated December 1994, the commission stated: ìBy comparison to the reports from other areas of the state and nation on this subject, Lincoln County School Districtís problems are comparatively minor, but growing.î The commission recommended several actions to the school board, most notably the creation of the Student Behavior Management Team, which would include representatives from each school and would be assigned the task of implementing the commissionís recommendations. The report also contained a recommendation to develop a ìsystem-wide early intervention processî for the primary grades, such as ìa K-2 curriculum dealing with school expectations, social skills development, and behavior consequences.î

In 1995, motivated by the understanding that issues of student behavior and discipline were a top priority for the community, Mary Riley, who was then a resource development specialist for the school district, set about identifying grant programs and special projects that could be implemented in the schools and addressing the recommendations made by the commission. She created an informal working group of teachers, administrators, and others interested in the topic to help her in her quest.

Late in the year, Riley came across a ìRequest for Proposalsî (RFP) for the Edward Byrne Memorial State and Local Formula Grant Program, which is administered by the Criminal Justice Services Division of the Oregon State Police. The purpose of the Byrne Grant RFP is to solicit applications ìfor grants for innovative projects to reduce violent crime and drug use and improve the criminal justice system.î The Byrne Grant RFP emphasized its interest in programs that reduce and prevent juvenile crime and described several model programs that were designed to achieve that end; the Resolving Conflict Creatively Program was one such program.

Interlude: Serendipity in the State Capital

The story of how RCCP came to be incorporated into the stateís Byrne Grant RFP also began in 1994. Around the same time that Superintendent Liebertz organized the Commission on Student Violence and Discipline in Lincoln County, State Attorney General Theodore Kulongoski took the helm of the newly created Governorís Task Force on Juvenile Justice in Salem, the state capital. At the time, according to a report issued by the task force, the stateís juvenile justice system was being overwhelmed by an increase in juvenile crime: there were more gangs, more guns, and more juvenile felonies than ever before. Between 1988 and 1992, the number of violent offenses committed by juveniles in the state increased by 80 percent.

Then-Governor Barbara Roberts charged the new task force with reviewing Oregonís Juvenile Code and recommending ways to overhaul the juvenile justice system in order to keep pace with the realities of juvenile crime. A number of significant reforms proposed by the task force in its final report, issued in January 1995, were approved by the state legislature and passed into law.

Reforming the juvenile justice system, however, was only part of the stateís plan to address juvenile justice issues. Another task force, again headed by Attorney General Kulongoski, focused on preventing juvenile crime. Specifically, the mission of the Governorís Juvenile Crime Prevention Task Force was to ìhelp reach Oregonís youth before they choose a path of crime.î This second task force, created and appointed by Governor John Kitzhaber, was ultimately responsible for RCCPís finding its way into the Byrne Grant RFP.

Although this second task force, appointed by the governor in 1996, made numerous recommendations, those that fall under the heading ìViolence in Schoolsî are most relevant to this report and are listed below:

- The Department of Education should require all school districts to implement conflict resolution classes for all K-12 students.

- All middle schools and high schools of any significant size should be required to establish student peer mediation programs.

- A curriculum for social skills development should be developed and implemented that would provide youth with basic skills, such as how to make friends and how to accept peers.

The recommendations of this second task force were not incorporated into specific legislation, but the three proposals listed above are now embodied in the stateís Byrne Grant program, which supports primary violence prevention in schools.

Overview of the Oregon Byrne Grant Program

The Edward Byrne Memorial State and Local Formula Grant Program is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Justice. Created in 1988 by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act and named after a New York City police officer who was murdered by drug dealers, the federal Byrne Grant program focuses on violent offenders and is intended to help state and local governments improve their criminal justice system. Each year, Congress appropriates the program funding, which is then allocated to state governments for distribution to state agencies. In Oregon, the Criminal Justice Services Division of the Oregon State Police administers the grant program.

In 1996, Oregonís Byrne Grant program was revised to reflect the stateís commitment to reducing and preventing juvenile crime. New priority areas were introduced and two million of the stateís six-million-dollar Byrne allocation was committed to juvenile crime reduction and prevention. According to the stateís 1996 Application for Byrne Funds, ìthe new Byrne program will target school-based violence prevention education, increased response to first time offenders, and services for repeat juvenile offenders.î Thus, three categories of juvenile programs became available for funding: primary prevention in schools; secondary prevention in communities; and tertiary prevention in communities, schools, and families. As its only example of a primary prevention program in schools, the application named RCCP.

According to Greg Peden, then director of the Oregon Criminal Justice Services Division, RCCP found its way into the RFP because it had been so highly regarded by the National Institute of Justice that it became the focus of a special report entitled ìBuilding the Peace: The Resolving Conflict Creatively Program.î The report states that ìRCCP . . . was selected for presentation after an exhaustive review of school-based [violence prevention] programs across the country.î

Back to Lincoln County: The School District Adopts RCCP

When Mary Riley, resource development specialist for Lincoln County schools, came across the Oregon State Policeís Byrne Grant RFP, her first task was to determine whether RCCP was appropriate for Lincoln County. She read in the RFP that RCCP had been recognized by the National Institute of Justice as an effective violence prevention program, but she knew nothing about how the program was structured, what it required, or whether it would fit the needs of her community. She also read that although the State Police Department considered RCCP to be a ìbest practicesî model, it also was willing to consider funding other violence prevention programs if the applicant community felt that a different program was more suitable to its particular needs.

Thus, she and the informal working group she had assembled set about researching RCCP and several other programs. Although several prevention programs had been proposed by members of the working group and the community at large, no one was familiar with RCCP. Riley contacted Linda Lantieri, director of the RCCP National Center in New York, and began what was to become a close and productive relationship. Lantieri told Riley that a teacher and former RCCP trainer from California was now working in the Corvallis County School District, which is adjacent to Lincoln County. Riley arranged for several representatives from Lincoln County to meet with the former RCCP trainer, who was able to give them a real sense of the program: how well it works, what it entails, and the challenges to its implementation.

According to Riley, when it came time to write the Byrne Grant application, ìThe decision to apply for funds to implement RCCP was essentially unanimous––the choice was obvious.î The groupís research determined that RCCP was the most comprehensive program of its kind, one that is designed not just to change the school environment but also to create a community-wide commitment to peace.

Drafting the grant proposal took several weeks. The completed application, which was submitted by Superintendent Liebertz in July 1996, included a definitive statement of need that highlighted the findings of a recent statewide study (conducted by Children First for Oregon, an independent nonprofit organization) that ranked Lincoln County as the worst county in the state for childrenís overall well-being. The study had compared all 36 Oregon counties according to numerous indicators, including school dropout rates, teen pregnancy rates, reported incidents of child abuse, and the number of referrals to the Juvenile Department. The study ranked Lincoln County near the bottom in every category.

The application also contained a written description of the school districtís plans for implementing and evaluating RCCP (see subsequent sections for more detail) and numerous letters of support from county and state organizations: the County District Attorney; the County Commission on Children and Families; the Oregon Department of Human Resources; the Newport Office of the Oregon State Police; the County Commission on Student Violence and Discipline; the County Juvenile Department; the Teen Court of Lincoln County; and the Oregon Coast Council for the Arts. The application also included a letter of support from the national office of RCCP.

ìIt was obvious from our application, from the letters of support we included, that the entire community was behind this idea 100 percent,î said Arlen Tieken, then director of education for the school district. ìWe put in a tremendous collaborative effort––from the school board to the District Attorney to various community organizations and agencies to individual parents, teachers, principals, and students––we all wanted this program.î

In October 1996, the school district was notified that it had been awarded an Edward Byrne Memorial Grant in the amount of $245,000 for four consecutive years to implement RCCP in its schools. According to Greg Peden, at least 10 counties submitted grant proposals to implement RCCP, but Lincoln County was the only one to receive a grant to do so. He cited several reasons for the decision: Lincoln Countyís obvious community-wide commitment to and need for the program; its thorough and detailed plan for implementing and evaluating the program; and the fact that Lincoln County was the only Byrne Grant applicant that had contacted the national office of RCCP directly to determine whether the program was a good fit.

A Closer Look at the Lincoln County RCCP

The Lincoln County RCCP––formally titled the Lincoln County Primary Prevention Project, but generally referred to as the Lincoln County RCCP––officially began October 1, 1996, when the school district was notified that it had been awarded a Byrne Grant. However, as the first yearís funding was not received until early 1997, the final months of 1996 were used for additional planning and preparation. During this period, a full-time project coordinator, Ellen Anderson, was hired. Anderson's commitment to RCCP is based on more than philosophical agreement; it is personal as well: a few years ago, her teenage son was physically assaulted by a fellow student at his high school. Anderson manages all aspects of the program, from implementation to community outreach to evaluation. The grant money that paid for her position gave Lincoln County an advantage over many of the 11 other school districts that do not have the funds to hire a comparable staff person for their RCCP programs.

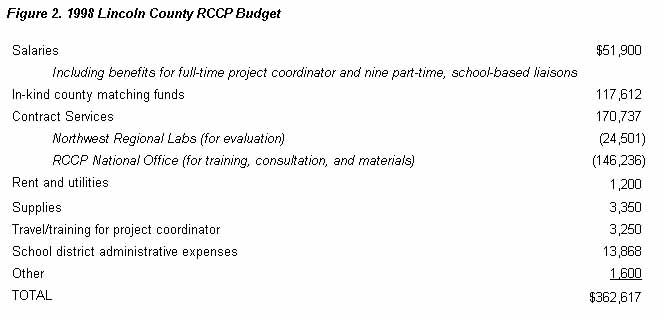

In fact, Lincoln County is the only school district of the 12 that are enacting RCCP whose costs are covered by a state Byrne Grant. Currently in the third year of a four-year implementation plan (see Figure 1), the Lincoln County RCCPís annual budget is approximately $362,000. Of that, $245,000 is supplied by the Byrne Grant funds; the rest comes from in-kind support supplied by the school district (see Figure 2). State Byrne Grant rules require that a grantee community supply 25 percent of the projectís annual budget through matching funds.

Lincoln County RCCP is using the four-year grant period to establish a self-sustaining program that can be maintained at minimal cost to the school district when the grant funds expire. To become self-sustaining, Lincoln County is bringing into play the standard RCCP components: training teachers, administrators, school staff, and parents in the RCCP concepts; classroom instruction for students; and a peer mediation program. The emphasis on ìtraining the trainers,î which enables local participants to become RCCP trainers themselves, frees up funds that would have been used to pay RCCP to send its professional trainers and consultants to Lincoln County each time a new group of teachers (or administrators or parents) required training. Instead, the school district will have its own set of fully qualified local trainers.

From the beginning, the plan has been to integrate RCCP into all 18 of the countyís schools during the four-year grant period. During the first year, volunteer teachers from the six schools that demonstrated the most interest in early participation were selected to receive RCCP training. Six more schools were selected through an application process to join the program in the second year; three schools were added in the third; and the remaining three will join the program in the final year of the grant. According to various school district officials, this stepped approach has been vital to ensuring the success of RCCP because it has enabled schools to join the program according to their own timetable, as they have felt ready and able to do so.

ìWe were anxious to begin the RCCP program at our school,î said Tom Zandoli, principal of Yaquina View Elementary. ìIt seems like most programs are ëcanned,í whereas RCCP seeks the internalization of peace; itís not into gimmicks, it offers something real and substantial to our students.î

Because RCCP is such a complex and comprehensive program, integrating it into one school, let alone an entire district, is a challenging task. Lincoln County has allowed schools to determine their own level of preparedness to take on this task in order to reduce the number of inevitable difficulties. Interviews with Lincoln County school administrators and teachers revealed a shared belief that the most challenging part of introducing RCCP into a classroom is the commitment of time it requires of a teacher.

Fortunately, some teachers in Lincoln County have discovered that, once they have integrated RCCP into their regular classroom routine, they actually have more time to teach. ìAs students have soaked up the concepts of RCCP,î said Grace Wiesner, a teacher at Waldport Elementary School who has been trained to instruct other teachers to incorporate RCCP in their classroom regimen, ìdisruptions due to students acting out, arguing, or talking back seem to have been reduced.î However, because the school district did not want to rely on the promise of such a benefit to motivate teachers, it launched a unique pilot program, which, if fully successful, would encourage a deeper commitment among teachers to implement RCCP in their classrooms.

The pilot program is developing social and emotional learning benchmarks, which would require students in grades 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12 to be judged on how well they have learned the socialization concepts taught through RCCP. The main idea behind the benchmarks is that if schools are to make true commitments to teaching students productive ways to handle anger and get along with others, then students should be held accountable for demonstrating that they are learning these skills.

RCCP is not just a school district program, however. Although schools are the obvious place to begin teaching students these fundamental skills, schools working alone can not make a big enough dent in changing societal norms. According to RCCPís Lantieri: ìFor schools and communities to reach out to one another, a porous boundary needs to be created between the two. Teachers, administrators, and students need to become part of the community life and schools need to let communities in.î To achieve this goal, Ellen Anderson is working with the RCCP Community Advisory Board to determine ways to integrate RCCP more fully into the entire community by taking the programís concepts outside school walls. For example, last year RCCP assumed the lead role in establishing a local chapter of the collaborative, statewide campaign entitled ìHands Are Not for Hurting.î During the campaign, which ran from October 5 to 23, 1998, more than 800 community members traced their hands and signed a pledge that states, ìI will not use my hands or words to hurt myself or others.î Some county businesses joined the campaign as well, declaring their offices ìviolence free.î For example, Pacific West Ambulance displays a ìHandsî bumper sticker on every ambulance and each of its 50 employees wears a ìHandsî button.

Anderson also arranged for the Accountable Behavior Health Alliance, a program organized by a coalition of four counties to provide mental health services under the Oregon Health Plan that is responsible for prevention efforts in Lincoln County, to sponsor a countywide parenting education program. The program, titled ìPeace in the Family,î has been in operation since the spring of 1998 and is based on the RCCP parent training curriculum. Peace in the Family conducts six-week parenting workshops for groups of 20 to 25 parents at the local schools, the housing authority, community sites, and in school buildings.

More recently, the Lincoln County RCCP formed a partnership with the countyís Head Start program and sponsored a training session for all the programís employees and other daycare and childcare providers around RCCPís Early Childhood Adventures in Peacemaking curriculum. Each of these efforts, as well as others like them that have yet to be implemented, is helping the Lincoln County RCCP to create ìporousî boundaries between the schools and the broader community and to integrate the concepts of RCCP into the daily lives of county residents.

Despite its broad-based community focus, much of the RCCP curriculum takes place in the classroom. The majority of the Byrne Grant funds are being used to train Lincoln County adults––teachers, administrators, parents, and others––in the concepts of RCCP so that they may, in turn, teach those lessons to the countyís children. What is it, exactly, that the children are learning?

The RCCP classroom curriculum, which has been introduced into 15 Lincoln County schools to date, is a K-12 curriculum that focuses on teaching students critical emotional and social skills: active listening, empathy and perspective taking, cooperation, negotiation, the appropriate expression of feelings, assertiveness (as opposed to aggressiveness or passivity), appreciation of diversity, and countering prejudice and discrimination. Teachers are strongly encouraged and asked to commit to teaching at least 25 or more RCCP lessons during the school year. Classroom lessons are tailored to the age of the students and include role-playing, interviewing, group discussion, brainstorming, and ìteachable momentsî that arise from real-life situations. Students also are taught how to appreciate cultural diversity and are shown ways to counter bias.

ìI am frequently reminded of the potentially enormous power that this instructional seed planting brings,î said project coordinator Anderson. ìThere are many children who take this instruction very much to heart and courageously make actual changes in their behavior when faced with conflict. They do this in the face of a culture that fails to support this ëway of being.íî

Once a core group of teachers in a school has been trained, the teachers begin introducing students to the RCCP curriculum. The elementary school curriculum (kindergarten through grade 6) offers 51 lessons divided into 12 units that stress experiential ìlearning by doingî activities, such as drawing pictures to illustrate concepts, writing stories, and role-playing. The middle and high school curricula (grades 7 through 12) build on the concepts taught at the elementary level. Effective negotiation, active listening, avoiding miscommunication, and recognizing prejudice are taught through written and role-playing exercises and classroom discussion.

In addition, once the curriculum has been solidly integrated into the school environment, a select group of students––generally from grades 4 or 5 on up––may be asked to become peer mediators. These students, if they agree, then receive special training in mediation skills, which enables them to help resolve conflicts in class, on the playground, in the lunchroom, or after school. To date, three Lincoln County schools have instituted active peer mediation programs.

Figure 1. Lincoln County RCCP Implementation Timeline

Year 1 (1996-1997)

Teacher training for teams from six schools

Monthly staff development––classroom visits for 35 teachers

Direct skill instruction for students in six school sites

Training of all school district administrators and community grant partners

Training of support staff from six schools

Parent education workshops in each area of the county

Collection of baseline data for evaluationYear 2 (1997-1998)

Teacher training for teams from 12 schools

Monthly staff development––classroom visits for 62 teachers

Direct skills instruction for students at 12 school sites

Parent education––12 workshops of approximately 25 parents each

Advisory Board training

Student pre- and post-program testing added to evaluation profileYear 3 (1998-1999)

Teacher training for teams from 15 schools

Monthly staff development––classroom visits for 100 teachers

Direct skills instruction for students at 15 school sites

Parent education––training of volunteer parents to conduct education program for parents

Training of local trainers, teacher mentors, mediation trainers

Implementation of peer mediation program at three schools

Creation of social and emotional learning benchmarks for grades 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12

School climate surveys conducted at participating schoolsYear 4 (1999-2000)

Teacher training for teams from 18 schools

Continued monthly staff development

Direct skills instruction for students at 18 schools

Completion of training of all local trainers

Expansion of peer mediation program

Expansion of social and emotional learning benchmarking pilot

Final evaluation results

Is RCCP Working in Lincoln County?

The short answer to this question, given by everyone interviewed for this report, is ìyes.î The citizens of Lincoln County––parents, teachers, administrators, students, and community leaders––like what they see so far. Teachers and parents alike are full of stories that illustrate how students who are being exposed to RCCP lessons, both in the classroom and at home, appear to be learning the skills of conflict resolution.

ìIn the past, Iíve had kids in my class be suspended for fighting, for bringing pocket knives to school, things like that,î said Debby Clark, teacher and student council adviser at Sam Case Elementary. ìBut since weíve introduced RCCP, the number of infractions have gone down and the kids donít fight as much.î

Dee Haddon, a parent who also helps out as a teacherís aide in her sonís classroom at Mary Harrison School, comments: ìIíve noticed changes in the kids, especially in the boys. Boys tend to get physical just like that, but since RCCP, Iíve noticed them choosing alternatives, they stop and think first.î

Students, too, are noticing the positive impact of RCCP. When asked what she has learned from RCCP lessons, a sixth grader at Waldport Middle School said, ìI have learned how to listen for cues that trigger my anger, and have discovered that it is best for me to calm down and walk away from conflict to keep it from escalating.î Another student at the same school said: ìThe biggest thing I learned from RCCP was ëI messages.í They help me focus on what people are saying and help me keep my cool. No one is accusing anyone of anything; we are saying how that person made us feel.î

Younger students are learning the same lessons. One student at Sam Case Elementary commented, ì[RCCP has taught me] to be kind to others.î A classmate said he has learned ìnot to make fun of people,î and another added that RCCP teaches students to ìresolve conflicts and instead of asking for a teacherís help, you can solve it yourself.î

These positive anecdotal assessments of the program support the findings to date of an ongoing, independent evaluation. Roy Kruger, who is leading the evaluation for the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory (NWREL) in Portland, Oregon, said: ìThe data clearly shows that the program is doing what it was intended to do, teaching students about resolving their conflicts. Both students and teachers report positive changes in student behavior and school climate. These findings strongly suggest that the Lincoln County RCCP will have a positive, long-term impact on lowering the level of juvenile delinquency in the district.î

The evaluation, which will document the actual achievements of the Lincoln County RCCP at the conclusion of the four-year grant period, began with the collection of baseline data in year one and also covers site visits to schools; interviews with administrators, teachers, and students; classroom observations; and archival and curriculum reviews.

Whereas the independent evaluation is being administered by NWREL, the overall evaluation of all sites participating in the Oregon Byrne Grant program is under the direction of the Oregon Department of Human Resources, which requires grantees to conduct both process and outcome evaluations. The purpose of the process evaluation is to monitor and assess whether a program is being implemented as planned and to ascertain that the grant money is being spent as intended. The purpose of the outcome evaluation is to determine whether the program is achieving the desired goals. This report will focus only on Lincoln Countyís plans for conducting the required outcome evaluation.

Outcome Evaluation Plan

Specifically, the Lincoln County RCCP outcome evaluation was designed to determine how well the program is meeting the objectives listed below, which were set by the state for funded primary prevention programs:

- To educate youth on the consequences of participating in violent behavior

- To prevent and address social conflict in schools

- To teach problem solving and anger management skills

- To promote personal and social responsibility among students

- To target local juvenile crime prevention benchmarks

Data on the first four objectives are being collected through ìpre- and post-program testî survey instruments; they include surveys of teachers conducted at the time they are being trained in RCCP and again at the end of the school year after they have taught the program in their classroom; and surveys of students conducted at the beginning of the school year (before exposure to RCCP) and again at the end of the school year.

To determine whether the program is having an impact on juvenile crime rates (objective 5), a series of ìperformanceî indicators, which research has suggested are related to juvenile delinquency risk factors, will be measured. These indicators include school attendance rates, incidents of school-related fighting, incidents of bringing weapons to campus, incidents of vandalism, school dropout rates, incidents of harassment, the number of school suspensions and expulsions, and the number of police visits to campus.

Preliminary Evaluation Results

According to NWRELís most recent evaluation progress report, preliminary results to date indicate that the communityís positive perceptions are accurate and that the program is performing very well. A number of specific findings have emerged from surveys of teachers: 99 percent of teachers reported that students were more cooperative; 91 percent reported that their studentsí ability to understand other points of view improved; 84 percent of teachers reported less physical aggression among students in the classroom; 82 percent of teachers reported that students had a more positive attitude toward school; 82 percent reported that students were better able to solve their own conflicts without adult intervention; and 77 percent reported that students resorted less often to name calling and verbal put-downs.

The report, in summarizing these findings, states that the Lincoln County RCCP ìhas made substantial progress in accomplishing its goal of helping students . . . become more cooperative, collaborative, and supportive of each other.î This is particularly true for elementary school students (see Table 1). According to the report, ìElementary teachers and students describe significant changes in student behavior and an increased willingness and spontaneity to solve their own problems with the conflict resolution skills learned through the program.î This is not surprising given the fact that elementary school teachers often have the entire school day to work with students, whereas teachers at higher levels generally have only 50-minute class periods to provide instruction in a specific subject area. These preliminary findings led Lincoln County administrators to explore ways to integrate the program more effectively in the upper grade levels.

These data are a preliminary indicator that the first four objectives are being met. The programís impact on juvenile crime risk factors, however, has yet to be analyzed owing to several limitations. Currently, individual schools are using an array of methods to record student disciplinary information, which is hampering data collection. In addition, not all schools have been able to differentiate in their record keeping between students who have received RCCP instruction and those who have not, which makes it difficult to determine whether RCCP is affecting the performance indicators. Records showing that 1,875 of approximately 6,850 students within the district were involved in RCCP during the 1997-98 school year suggest that the indicators may have varying degrees of relevance to the actual changes that are taking place in district schools. The school district currently is working on a computerized management information system that will resolve these problems.

Conclusion

Violence in schools currently is a hot political topic. In response to the rash of homicides on school campuses during the last school year, federal, state, and local governments are considering a variety of programs and solutions that seek to make our still relatively safe schools even safer. The residents of Lincoln County, Oregon, began such an effort almost five years ago. Today, it has almost achieved its goal of implementing the Resolving Conflict Creatively Program in all 18 schools in the county.

Before it began, there was some question as to whether a complex, comprehensive program like RCCP, which was developed in the New York City Public Schools, was even necessary in a small, rural community where juvenile violence was a comparatively minor, but growing, problem. It was determined, however, that such a program––one that seeks to change not only the entire school environment but societal norms within the community as well––is precisely what was needed to truly engage the community in preventing violence among young people.

Currently, in its third year of a four-year implementation plan, the Lincoln County RCCP is working well. Preliminary evaluation results demonstrate that young peopleís behavior is changing. They are more cooperative in class, are acting out less and getting into fewer physical and verbal fights, and are more supportive and empathic toward their peers. And the community is extremely enthusiastic about the program. Jeanne St. John, co-chair of the Student Management Team and principal of Mary Harrison School, comments: ìThis program has required the community to work together in ways that it hasnít before. It touches people profoundly and gives them a sort of hope for the future that more mundane programs just canít offer.î

Often, school systems feel their hands are tied when it comes to introducing new programs, usually because education budgets are so tight. Lincoln County, however, was not deterred. The county was able to implement a much-needed program through a state grant program for preventing juvenile crime and violence that directs federal funds to all 50 states for the purpose of addressing crime and improving local criminal justice systems. Although the Lincoln County officials interviewed for this report stated that, without the Byrne funds, the county would not have been able to develop RCCP to its present level; their view is countered by representatives from the Oregon governorís office, who named various state resources that could be tapped to help a locality support this type of program. The challenge for communities and state governments across the country is to close this information gap––to find the dollars and to engage the communityís good will––and, by so doing, to help thousands of children learn how to resolve conflict and promote peace and health in our communities.

(To request a bound copy of this report, click here.

To see a complete list of Milbank reports, click here.

Be sure to specify which report you want,

your name, mailing address, and phone number.)Milbank Memorial Fund

645 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10022

(c) 1999 Milbank Memorial Fund. This file may be redistributed electronically as long as it remains wholly intact, including this notice and copyright. This file must not be redistributed in hard-copy form. The Fund will freely distribute this document in its original published form on request.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 1-887748-30-X